Washington Kurdish Institute

April 21, 2023

After two decades of misrule, Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is on the verge of losing his power in the runup to presidential and parliamentary elections on May 14, 2023. Erdogan first gained power in 2003 amidst economic turmoil and public dissatisfaction with the government led by nationalists and socialists. As a young politician, Erdogan became the mayor of Istanbul and gained national attention after being removed from office by the government for allegedly inciting religious hatred. Despite a subsequent political ban, Erdogan was able to form his own Islamist party, the Justice and Development Party (AKP), after Turkey changed its political ban laws. The AKP was established by Erdogan and his colleagues following the country’s economic collapse in 2001 – largely caused by political instability. Erdogan was able to capitalize on the chaos created by previous secular ruling parties, who had governed Turkey since its inception as a modern nation following WWI.

Erdogan’s early years in power were marked by economic reforms; the public was not concerned with his religious background or ambitions, but rather with the economy and unemployment relief. Erdogan popularly rose to power in Turkey’s semi-democratic electoral process; a process that never afforded that opportunity to the Kurds. Alongside economic reforms, Erdogan engaged with the Kurdish Question and launched a peace process with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). He later abandoned this process, however, after he was deeply disappointed with the Kurdish refusal to grant unconditional support to his autocratic government. He then switched gears and aligned with ultra-nationalist parties who were opposed to Kurdish reconciliation.

After years of Erdogan’s mismanagement, the value of the Turkish Lira dropped, hitting historical lows on several occasions. He broke records for leading through the most dire unemployment in history while significant corruption cases chased him and his family. Above all, his authoritarianism resulted in the incarceration of thousands of people – mainly Kurds, journalists, academics, and anyone who opposed his party. Erdogan and the AKP used the term “terrorist” against anyone challenging his tyranny. Eventually, in Erdogan’s Turkey, everyone became a terrorist.

Regionally, Erdogan’s former right-hand man, Ahmet Davutoğlu, who served as prime minister and foreign minister, bragged continuously about his “Zero Problems with Neighbors” policy, which ended up creating problems with all of the country’s neighbors. In fact, under Erdogan, Turkey got involved in several regional issues, resulting in Turkey’s isolation and uniting dozens of countries against his administration. The country’s reputation has taken a significant hit over the last 20 years, marred particularly by ethnic cleansing and invasion campaigns Turkey has pursued against the Kurds, internally and in neighboring Syria and Iraq. At the same time, Turkey’s expansionist policy has stretched the country’s resources to an unsupportable level, driven by its involvement in Syria, Libya, Africa, and the Azerbaijani war on Armenia’s Artsakh.

For Erdogan, wars are critical before elections

Erdogan’s peace process with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) was designed to benefit him rather than solve the century-old issue. The Kurds, up to this day, want a solution from the bottom to the top in Turkey’s institutions, as the problem is not with a leader but with a state that has systematically persecuted and oppressed a nation and people. Preferring political flexibility to progress, Erdogan depended on his intelligence chief, Hakan Fidan, to launch a peace process that he could end at any moment. Once the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) presented a first setback for him and his AKP party, Erdogan terminated the popular process entirely. After years of negotiations, even Turkish opposition lawmakers came around to support the peace process, but for Erdogan, votes from AKP supporters were the goal.

Soon after allying with the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), Erdogan sought a familiar and vulnerable scapegoat to provoke increased nationalist fervor and rally around the flag: the Kurds. Erdogan shrewdly observed that sovereign countries – like Greece, which continues to struggle with Turkish provocations – are a much harder military target than non-state actors. Instead, Erdogan has cracked down on the Kurdish minority in Turkey in recent years. This crackdown has included the arrest of Kurdish politicians, journalists, and activists, as well as the closure of Kurdish-language schools and media outlets using poorly-defined anti-terrorism laws with an unacceptably wide purview. Erdogan used wars against the Kurds to win two elections and a referendum as he successfully pushed nationalist arguments that the weak Turkish opposition could not match. Erdogan’s war involved the destruction of Kurdish towns in Syria and three ground invasions against the Syrian Kurds. Following the initial border incursions into Kurdish autonomous territory in Syria, Erdogan occupied and reinforced a large swath of land in Iraqi Kurdistan under the pretext of fighting the PKK.

Since 2021, Erdogan has repeatedly threatened the Syrian Kurds with a new invasion in order to boost public opinion in his favor ahead of elections. He never stopped bombing the Syrian Kurds, however, and had to reorient his attention towards massive earthquakes that hit the country just days before his plans to invade the Kurdish-led self-administration in Syria. The earthquake distracted the region, and Erdogan fell into big trouble as his government failed to deliver aid to those affected. At the same time, investigations revealed that Erdogan had relaxed enforcement of building codes in recent years, causing 160,000 buildings to collapse or be severely damaged. Moreover, his reopening to Syria’s dictator, Bashar al-Assad, after a decade of conflict kept Russia from allowing Turkish invasion plans to proceed. While unable to invade Syria, Erdogan still beat the war drums, targeting the commander of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Iraqi Kurdistan in a desperate assassination attempt that further stoked Turkish nationalism at home.

The Kurds are again the kingmakers in Turkey, but Erdogan will not sit idly by

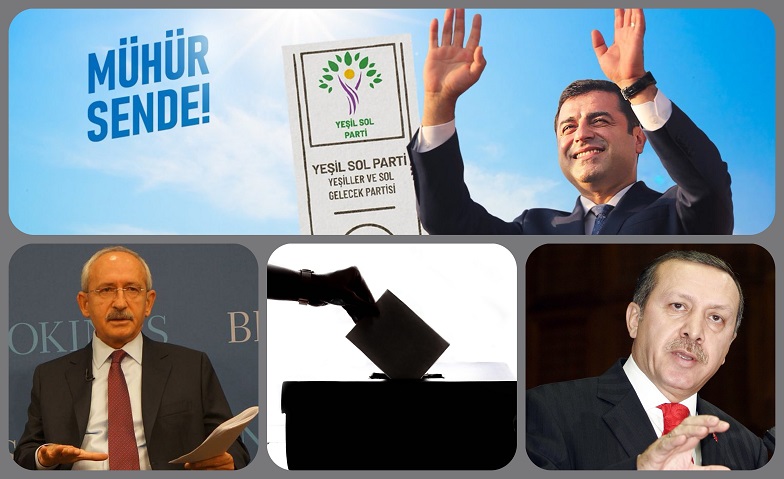

In Turkey’s divided political landscape, the Kurds have been the tiebreaking element. For example, Erdogan received immense support from Kurdish voters when he proposed openings to the Kurdish nation in his early years. In 2019, the opposition candidate of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) for Istanbul mayor, Ekrem İmamoğlu, won as a result of Kurdish votes against Erdogan’s chosen candidate, Binali Yıldırım. Currently, the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) and its newly established party for the upcoming May elections, the Green Left Party (YSP), are also supporting the CHP’s presidential candidate, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu – a move that could net the latter the winning ticket. Unlike previous elections, the HDP has annulled plans to have a presidential candidate in direct support of Kılıçdaroğlu.

While the opposition leader faces several challenges, Erdogan will not sit quietly to see Kurdish votes go to Kılıçdaroğlu and lose his power. Currently, the HDP and Kurdish politicians face prosecution on sham charges which seek the closure of the entire party. If 108 politicians are banned from politics in the ‘Kobani trial’ case, Kurds will surely face an uphill battle just days before elections. Kurdish representatives face a potential loss of votes and may worry that some Kurds will refrain from voting in protest. Erdogan’s record of electoral interference has drawn international attention: he and his party have been accused of rigging votes and creating a chaotic electoral atmosphere for the AKP to exploit. Erdogan can easily manipulate the elections in a close election, which is the case on May 14. Rigging a single-digit vote to win another six years of power is undoubtedly the mark of a dictator. Nonetheless, if the margin with Kılıçdaroğlu increases to the double digits, then it will become much harder for Erdogan to get away with heavy-handed vote manipulation. When it appeared that he would lose an election to the HDP for the first time in 2015, for example, Erdogan launched a war on the Kurdish region, preventing thousands of people from voting in the rerun election, which resulted in AKP victory.

Turkey has a complex political landscape, and elections in the country are highly contested and often unpredictable. Erdogan has historically been a dominant figure in Turkish politics, and he has been the worst Turkish leader for the Kurds in decades. Voting for the main opposition’s Kılıçdaroğlu is also a risk for the Kurds, since the CHP has periodically stood with Erdogan during his campaigns against the Kurds. However, Turkey’s Kurdish nation has nothing to lose by choosing the lesser evil. The hope is that Kılıçdaroğlu will deliver on his promises to open up to the Kurdish Question and release thousands of Kurdish political prisoners held illegally by the Turkish state. To ensure that Kılıçdaroğlu will not continue Turkey’s anti-Kurdish policies, the United States and the European Union (EU) will be essential in collaboratively presenting a real plan to help Turkey return to good governance and improve its economy. A plan should be conditioned on Turkey making peace with the Kurds, who have the oldest and most global struggle in the world.

Before then, proper monitoring by international organizations and the United Nations is a must to ensure a transparent election takes place, with clearly-defined consequences for election tampering. Erdogan’s underhanded tactics may succeed in the absence of international pressure and real observance of the election. History should be our guide: appeasement by the West toward Turkey has failed. We must choose progress.