Washington Kurdish Institute

By: Matthiew Margala March 5, 2021

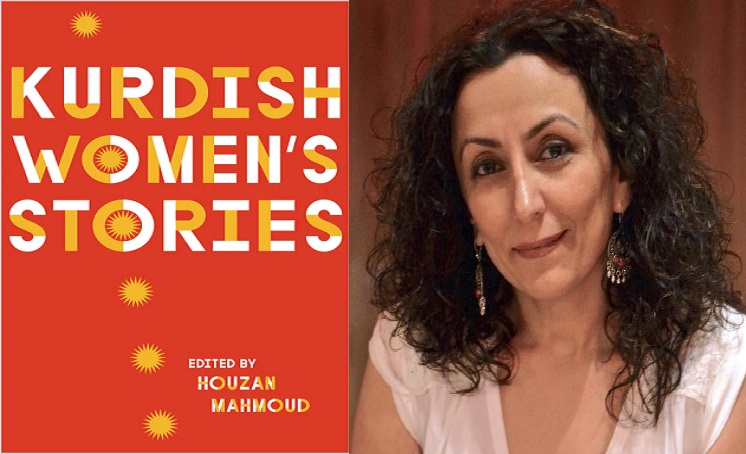

The Washington Kurdish Institute (WKI) interviewed Houzan Mahmoud. Ms. Mahmoud is a Kurdish feminist, writer, public lecture, and anti-war activist. She is the co-founder of Culture Project, an online and print magazine that gives a platform to Kurdish voices. She has written for the Guardian, Open Democracy, Independent, and New Statesman.

During the interview, she discussed her newly published book, Kurdish women’s stories, the stories of women who lived, worked, and struggled in Kurdistan.

What inspired you to publish this book when you did at this point in time?

Well, I’m a Kurdish woman, first of all. I have been through a lot that many other Kurdish women have been through it as well. And there are a lot of studies and reports and journalistic reports and articles and documentaries and so on, but I think it’s not enough really to show who Kurdish women are. And I think Kurdish women, generally speaking, are under-researched, underrepresented, and sometimes misrepresented as well. So I thought it would be a good idea to actually get Kurdish women to write about themselves and the story of their lives beat: exile, imprisonment, political activism, clandestine activism, armed struggle, love, loss of loved ones, art, literature, and poetry. So I thought displacement as well, and their encounters with genocide, with assimilation policies of different governments in the Middle East, and so on. So I thought it would be a good idea to include the authentic voices of Kurdish women themselves, and that could be done through a book. And that’s why we have voices of 25 Kurdish women collected and written, and it’s published in Kurdish Women’s Stories.

Why was it important for you to include stories from all four parts of Kurdistan?

To me, there’s only one Kurdistan and that’s despite the fact that it has been over a century that we are divided and that division and colonization created a lot of problems for us. We want to really cut across those artificial borders and just to show the world that, these are our stories, no matter where we are, we are still struggling and surviving and trying to fight for our own rights as a woman. But also we are faced with various dictatorial regimes in addition to the two latest Islamic State of Iraq and Syria invasion, and attack on both Iraqi Kurdistan and Syrian Kurdistan as well.

How hard was it for you to bring together all of these stories? Because there are many of them in the book and they’re from all over Kurdistan and in some parts of Kurdistan, you have significant repression and I can imagine it can be difficult to get all these different stories. So was it difficult for you?

I think it was difficult in the beginning because I wasn’t really sure if Kurdish women would be willing to write about themselves because it’s a very personal thing. And then, generally speaking, I mean, I, myself, I’ve never thought about writing about myself, for example. And even later I started to speak about certain things that happen to me, in my country. So I just thought I should still do it. And then it was not only me and we were a good team of activists as well and writers and people translators who started this journey and we managed to collect those stories. In fact, later on, it became easier because we could tell that there’s a need for this. And then the woman who came forward to voluntarily provide their stories. They were just so happy that at the end, they got these stories published and not only in Kurdish, but also in English as well.

When you compare the situation for Kurdish women today in 2021 to that of Kurdish women, historically, what similarities and what differences do you see in how far they’ve come in terms of women’s rights and also Kurdish rights that intersectionality that they face?

I think in terms of repression by various States and war and the threat of genocide has, unfortunately, It’s a recurring theme. I mean, it’s always there unfortunately and Kurdish people, including women from time to time, get objected to genocide and the process of assimilation in those countries, cultural, I would call it linguistic and cultural genocide as well in parts like Turkey, Iran, and Syria until lately. And Iraq as well, like in Barshur (Southern Kurdistan or Iraqi Kurdistan) we have had to fight to be able to keep speaking in our own language and writing and be educated in that language. So those things are still a very big struggle, but there are other things that have changed like there’s a little bit of openness. And then we have South Kurdistan where there are relatively active cultural scenes as well that we can reach out to other parts of Kurdistan.

In terms of, uh, awareness, I would say among Kurdish women, it is much more different than before. Of course, they have more access to education and writing, and employment outside compared to many decades before. And to the outside world as well, because we were suppressed in silence and then nobody could hear us, and then nobody could know about our stories. And of course, because of the new technology as well people locally can report their own issues and on there, on the violation of human rights that is happening in those parts of Kurdistan. So I think things have changed in that sense, but unfortunately killing execution, imprisonment, genocide, and war, and never-ending conflict are still there.

Do you think that they’ve changed in all the different countries that Kurds find themselves to the same extent? Or do you think that it’s gone at a different pace depending on the location?

I think depending on the location. I’ve said before, as well in my book launch that it’s not because we are different. No, it’s just because the urgency of particular situations makes certain parts of Kurdistan respond differently toward different regimes. For example, Rojava, look at it. They had to defeat ISIS. Then now they’re faced with Turkish genocide and lots of other issues in Iraqi Kurdistan. There are a lot of problems as well. And in East Kurdistan and North Kurdistan, you can tell what the government is doing to the Kurdish population. So I think each part has its own specificity in terms of its own problems with their government, the colonizer basically. It makes it different from one part to another, but generally speaking, there is a good self-consciousness among Kurdish women in all parts of Kurdistan and that there are different struggles, but as well as solidarity and support between the four parts as well. And that’s what this book tries to do as well to achieve that no matter where we are, we are Kurdish women are in solidarity with each other, and then our stories are very similar as well.

Based on my own experiences in Kurdistan, I’ve found that Kurdish women, especially when I was in Rojava, do not necessarily take the same approach to feminism as women in the West have. In what ways does the feminism of Kurdish women differ to that of Western women and what can be learned here in the West from the approach that Kurdish women have taken, especially in light of the women’s revolution in Rojava?

I think the women’s revolution in Rojava is very unique and it’s much needed because it has revolutionary elements that put women in the center of politics and what we see not only in the West. But in many countries around the world, with the corporatization of women’s struggles and with the new liberalism as well, there’s the problem of NGO-ization. That in women’s movement is divided between values, little NGOs, depending on funding and programs. It’s all like becoming uniform. And really they’re going much further away from the actual daily struggles of women’s issues. And that what the struggle is telling us about women’s questions is that women’s issues are political issues and that it has to be fought through a political struggle on a social level and political levels. All levels, really not only through little NGO’s head, and they’re all through corporatization of the woman’s question, depending on funding and programs that don’t even fit the local problems and issues suffered by Kurdish women. I think there’s a deep politicization of women’s question at the moment under women’s movement, worldwide speaking, but we really need to re-politicize the women’s movement and to bring back the woman’s issues and the women’s movement into the center stage of politics. And to look at it as a revolutionary political struggle, not only as little offices here and there, with hierarchical systems and divisions and corporatization that doesn’t really solve women’s issues. In my opinion.

It’s often said that the Kurdish people’s own internal divisions are their worst enemy and the stories in the book are extremely varied in terms of their location and in terms of their content. So how can Kurds regardless if they are in Rojava, Bakur, et cetera, regardless of what political party they may support, overcome their differences and unite in the face of continued hostility by oppressive regimes?

Well, I think some of this division is also to do with both local players as well as international players. So that is not welcomed. And the majority of Kurdish people do not like that. This is between political parties vying for more power and influence. And also there are, as I said, local and regional, and international players behind it, which is not welcomed and that Kurdish women have a role to play as well in terms of cutting across those divisions those segregations basically, and the fact that we’ve been struggling for over 100 years for basic rights, the right to existence and the right to be who we are. It tells a lot about the level of resilience and struggle and resistance by Kurdish people, including women, that they have been waging this war against this division, as well as against, other interventions in our affairs.

You spoke to women of many different ages in the book as well, and there are women participating in the revolution Rojava, but also in other parts of Kurdistan in politics, in protest of all ages. Do you see a generational gap between the younger Kurdish women and the older Kurdish women who may have not had faced the same political situation? They may not have grown up with the Kurdistan autonomous region in Iraq or the Rojava revolution. Did this affect their mindsets at all?

I think there were differences, obviously for someone who was born 70 years ago is very different from someone who’s 20 years old or 25 years old. I mean, still, really there are a couple of themes that run through the book from the beginning to the end, through all these generations. And that is the problem with war, with conflict, with patriarchy as well. So yes, there are differences, but also similarities, and that you can tell towards the end that the younger generation of women in old parts of Kurdistan is much more aware of gender-based violence and how to fight against patriarchy in Kurdish society. They are talking about their awakening basically as a woman and how to find these ills as well. Whereas the older generation, because really the political situation was much more severe. And that the only thing you had to kind of cling on was to survive and to stay alive and to be after your loved ones, wherever they are, imprisonment, and lots of other issues. But we also have a couple of young girls from Rojava who wrote their stories and they’re telling again, experiencing again the invasion and occupation by ISIS and Turkey. So, yes, in some parts they’re still struggling with all of these problems that we have struggled with before in terms of war and conflict and so on. So, unfortunately, as I said in the beginning that the threat of war is always there of occupation of forcing you out of your land and genocide and assimilation. Unfortunately, most of these things are still happening in different parts of Kurdistan.