Washington Kurdish Institute

November 10, 2020

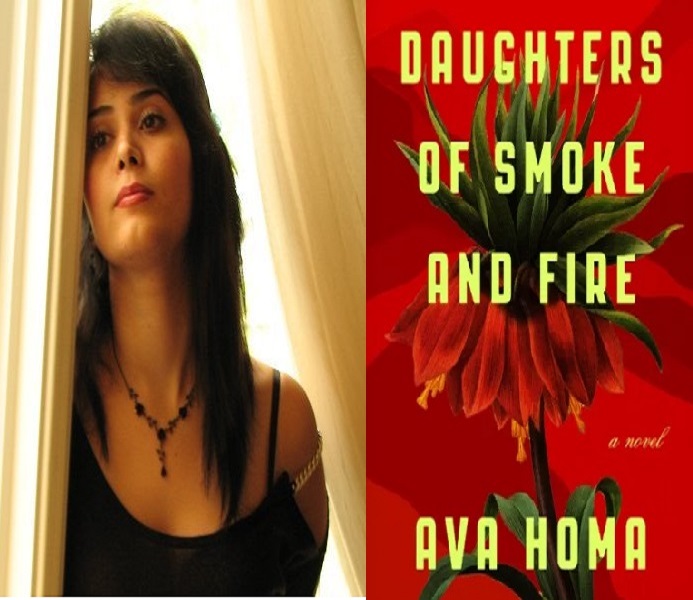

The Washington Kurdish Insinuate (WKI) interivew the Kurdish activist and writer Ava Homa. Ms. Homa spoke about her novel Daughters of Smoke and Fire and the Kurdish question.

Daughters of Smoke and Fire

The unforgettable, haunting story of a young woman’s perilous fight for freedom and justice for her brother, the first novel published in English by a female Kurdish writer

Set in Iran, this extraordinary debut novel takes readers into the everyday lives of the Kurds. Leila dreams of making films to bring the suppressed stories of her people onto the global stage, but obstacles keep piling up. Leila’s younger brother Chia, influenced by their father’s past torture, imprisonment, and his deep-seated desire for justice, begins to engage with social and political affairs. But his activism grows increasingly risky and one day he disappears in Tehran. Seeking answers about her brother’s whereabouts, Leila fears the worst and begins a campaign to save him. But when she publishes Chia’s writings online, she finds herself in grave danger as well.

Daughters of Smoke and Fire is an evocative portrait of the lives and stakes faced by 40 million stateless Kurds and a powerful story that brilliantly illuminates the meaning of identity and the complex bonds of family, perfect for fans of Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun.

Book link HERE

Interview Summuray

Matthiew Margala: Why did you decide to write the book at this time?

Ava Homa: Well, I mean writing a book is not something that you can, at least fiction, or at least writing fiction for me, is not something that I do because of a specific period of time. Actually, when I started writing this book, the world didn’t know the Kurds, the way they know us now. This, my writing, starting the book in 2010, goes back to before Kobani and before people saw a different side of Kurds because in the nineties they saw us as victims. And then after Kobani, there was a new picture of us. But when I started in 2010, no one had heard of Kurds. In fact, when I would introduce myself to Canadians as a Kurd, they would ask me most often to repeat and they wouldn’t understand. And they would even say things like “what, Turkish?” like no, Kurdish. So, also I basically invested in the timelessness of literature and the power it has through ups and downs and different decades in different periods of history to carry a timeless message and create a connection between humans across borders and race and time and decades and all of that. So it wasn’t really a matter of time. It was just something I had in my heart. It was a story that hadn’t been told. It was an authentic story. And I felt compelled to say this story the best way I can.

Matthiew Margala: Is the Western Media’s portrayal of Kurds beneficial for the Kurdish cause?

Ava Homa: It’s always better to be known, than to be unknown, but the problem with the media portrayal of Kurds is that it’s very one-dimensional, you know. I know in the Western world, there’s a binary of victim and survivor, and don’t be a victim, be a survivor and claim your identity and take hold of your life. And the fact is that we are both victims and survivors. We’re both at the same time. The other thing is, a lot of times you’re asked if, like I’ve seen in interviews where the authors and artists and filmmakers are asked, if they’re proud of their identity, and I save the word pride for what you have worked hard to achieve and not something that is simply an accident of birth. And that’s the moment when in Daughters of Smoke and Fire, my main character gets to say, I don’t like to be pitied. Like I don’t like to be seen as a victim. I don’t like also to be looked up to or looked down to, like, we see Kurds are either hailed as these superhumans, so different from the rest of the Middle East, fighting the evil of Daesh, which is absolutely true. And then we also have these people who have lost everything because of genocide. That portrait is also true, but between both of these portrayals, there is a whole spectrum of Kurdish voices with different views and ideologies and diversities. And what I really hope for the Western world to understand is that just like any other group of humans, we Kurds are complicated and funny and awkward and just everything that every other group of humanity is. I feel like with minorities, we’re always misrepresented, we are either hailed as superheroes or seen as this absolutely powerless people. And I just hope and wish that Western media would be capable of seeing us in all our shades and in all our abilities and limitations. And when you’re accepted with everything, that’s when you are seen, that’s when you’re understood and respected, but as long as you’re just some exotic thing that no one knows about that when you’re presented, you’re presented as either that extreme of victim or that extreme of champion.

Matthiew Margala: Do you believe there’s reason to be optimistic about the future of Iranian Kurds, and also Kurds overall?

Ava Homa: Again, I can only say that I’m cautiously optimistic. The reason Kurds in Iraq and in Syria got a chance to show the world who they are is only after the iron fist of Saddam Hussein and later Bashar Assad was removed. And then the question remains, how much would the Iranian Kurds be able to show who they are once Khomeini or like, the overall Islamic Republic’s iron fist is removed. For now, Kurds are heavily suppressed, heavily oppressed in Iran. And like you said, the world doesn’t know about it either, but what’s going to happen? We’ve seen that all these dictators have expiry dates, no matter how powerful they are and how invincible they seem at the time, they are guaranteed to have an expiry date. The government of Iran is dealing with so many problems inside the country with a terrible economy and a lot of protests and unhappiness and outrage that’s simmering constantly and sometimes boils over day in and day out, on one hand. And on the other hand with its horrible international reputation and everything that it’s doing in the region and outside. So with all this pressure inside and outside of it, especially with the crippling sanctions that have limited their sources of funding all these terrorist groups in the region, they’re looking at a very bleak future. So they do have an expiry date for sure. It just is a matter of when, which very much depends on, it’s a political thing. You can never predict when it’s going to happen. In 2000, we didn’t think there would be, you know, Saddam Hussein would be toppled in 2003. He seemed so invincible at the time. So that will for sure happen. And then Kurds in Iran, then will have the same recognition as Kurds everywhere and in a way, Daughters of Smoke and Fire, did that job and filled that vacuum. That emptiness that exists in terms of, are there Kurds in Iran, how many are there, what’s their life like? And so I took it upon myself to basically give a voice to not only the Kurds, who are voiceless in general, but specifically to Iranian Kurds, who are the most voiceless among the Kurds.