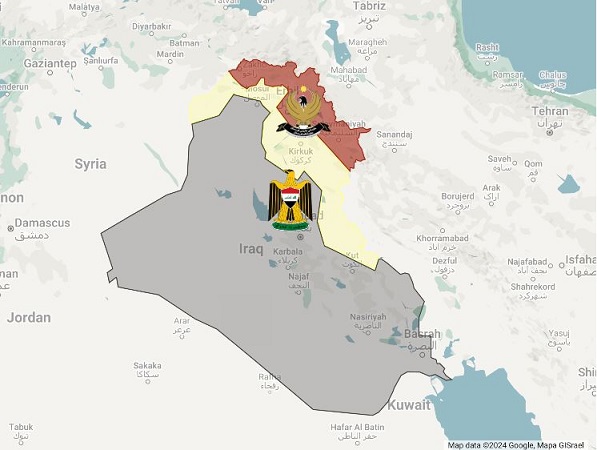

The Iraqi Constitution, made following Saddam Hussein’s defeat and ratified by popular vote, intended to decentralize the extensive powers accrued by the Ba’ath government. This Constitution aimed to empower regional governments and normalize territories undergoing extensive government-sponsored Arabization. Almost twenty years after the Constitution’s adoption, the federal government has consistently sidestepped its constitutional obligations. It now seeks to consolidate control over areas designated for regional governance. Most notably, it has failed to facilitate mechanisms for disputed territories like Kirkuk to determine whether they want to remain part of the federal government or join the Kurdistan Region.

Baghdad has also neglected—and at times reversed—its duty to normalize those disputed territories. Moreover, the federal government has rolled back the regional government’s autonomy, curtailing the hard-won concessions during the two-year constitution-making process.

Kirkuk

Kirkuk lies on the Khasa River’s east bank, a Tigris tributary. Erbil is to the province’s north, Baghdad to its south. Beneath Kirkuk’s surface is a vast oil reserve, making it a crucial area for Iraqi oil production and exportation. According to the 1957 census—the last reliable one—Kurds are the largest group in the province.

In 1968, Baghdad chose to Arabize Kirkuk. To that end, the central government deployed several techniques, including the “forced deportation of residents, confiscation of property, and the manipulation of administrative boundaries.” The government also relocated Arab tribes to Kirkuk, providing them housing and government benefits on arrival. On top of that, the government added surrounding Arab districts to Kirkuk, thus turning the majority Kurdish province into a majority Arab. An estimate provides that the federal government expelled over 100,000 Kurds, some Turkmen, and Assyrians from 1991 to 2003. Uprooted Kurds were sent to government-run camps. And those who stayed were forced to “correct” their nationalities: Kurds, Turkmen, and Assyrians had to give up their identities and register as Arabs. The Al Ba’ath regime also targeted these groups’ property and finances by, among other things, seizing assets and residences, allowing them to sell their real estate only to Arabs, and precluding them from buying property in the city.

That systematic Arabization ended in 2003 with Saddam Hussein’s and his government’s defeat. Two years of constitution-making followed, overseen by the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA). The Transitional Administrative Law (TAL) emerged during that process. This was a temporary constitution pending the popular ratification of a permanent one. TAL Article 58 aimed to redress the Arabization of Kirkuk. It provided for the restoration of individuals’ properties and homes, the relocation of those who had left Kirkuk because of the federal government’s policies, and the resettlement of individuals who the government brought into Kirkuk. It would also create new employment opportunities for those denied work so that they would leave Kirkuk, repeal nationality decrees, and give individuals the ability to determine their nationality and ethnicity free of duress or coercion. Complementing these were a valid census and a resolution over whether the disputed territories wished to join a regional entity or remain under Baghdad’s authority. These measures became known as normalization. When the Iraqi Constitution was adopted in 2005, Article 58 was incorporated into that document through Article 140. It stipulates that the Iraqi federal government will pursue normalization in Kirkuk, conduct a census, and hold a referendum for all disputed territories on whether to join the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). All were to be undertaken by 2007. None have. In short, Baghdad has flouted its constitutional obligations.

More to the point, since 2005, Baghdad has sought to consolidate its hold over Kirkuk and other disputed territories. Consider Baghdad’s suspending elections in Kirkuk and refusing to adequately fund the province’s government. And in 2018, the province’s acting governor pursued—with federal backing—Arabization like that under Saddam Hussein’s regime. For example, Arab settlers were brought back to Kirkuk to take over Kurdish lands. In 2022, the federal government turned its consolidation toward Kirkuk’s Kurdish and Turkish farmers through Decree 320. That order concerned agricultural lands the Ba’ath regime had confiscated in 1975. Had Article 140’s commands been implemented, those lands would have been returned to the original owners. Instead, the federal government kept these. It now seeks to put them to federal use. At the bottom, Baghdad departs from normalization and moves toward federal control and Arabization.

In March 2023, the federal government deployed yet another tactic targeting Kurds in the province through Article 37. This law stripped almost 100,000 Kurds of their right to vote. Yet that was not all: Days later, the federal government raided and seized shops in the Khan Khurma market. The government made shop owners leave and relocate—without compensation or lots in another location.

More than a year later, chaos prevails in Kirkuk. In May, Arab families camped on farmlands originally belonging to Kurds, expecting federal support for their claims. Kurdish landowners with titles to these lands were ignored. Although the encampment was removed and Kurdish farmers were permitted to harvest their lands, the core issue remains unresolved. The federal government’s failure to carry out Article 140 and achieve normalization means that disputes persist, disadvantaging Kurds in the province, who find the system stacked against them.

Rolling Back Federalism

And yet, Baghdad’s failure to realize constitutional directives extends beyond the disputed territories. Consider Articles 111 and 112 of the Iraqi Constitution. The first grants oil and gas ownership to “all the people of Iraq in all the regions and governorates.” The second provides for a joint enterprise between the federal government and regional governments to allocate revenues “in a fair manner in proportion to the population distribution in all parts of the country.” These articles are vague. And so, they require laws to effect their mandates. But the federal government has ignored that prerogative. When the KRG moved to export its oil and bring in revenue, the federal government managed to block sales through an international tribunal—impairing both Iraqi and Kurdish economic growth. This move marked the latest in a series of retaliatory devices the federal government has deployed in response to the KRG aiming to export its oil.

The federal government has also held up salaries for security forces and civil servants. In so doing, Baghdad has imperiled the KRG’s security, especially in light of an ISIS resurgence. And Baghdad has hobbled the KRG’s governance by refusing to pay its civil servants. In essence, Baghdad seeks to centralize more and more control and upend regional governance.

In sum, the federal government in Baghdad has vitiated the constitutional arrangement set in 2005, in which regions would enjoy greater self-governing powers and in which disputed territories would be returned to pre-Arabization times and choose whether to remain part of Iraq. Turkey and Iran are assisting Baghdad’s efforts. These two countries tend to support Iraq’s cracking down on Kurds and, in so doing, facilitate centralization.

The federal government must implement those constitutional mandates and respect the boundaries federalism demarcates. If it does not, the constitution-making process was for naught, and there is no significant difference between pre-and post-2005 Iraq. Iraq might require international encouragement to implement those commands. However, the problem is that the international community appears to be satisfied with the current state. The issue with this posture, however, is that when the situation boils over, all the international community does is note their regret. For example, one such regret was the U.S.’ failure to be starker about Iraq’s implementing Article 140. At the bottom, the international community must be proactive and ensure that those hard-negotiated constitutional provisions are finally implemented nearly two decades later.