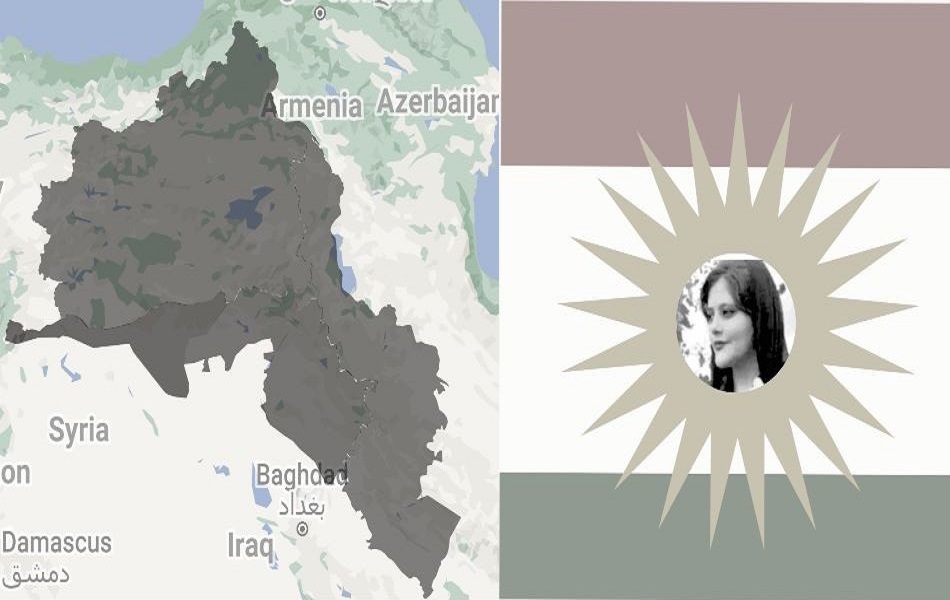

The outrage sparked by the brutal murder of Jina Amini at the hands of the “morality police” in Tehran, Iran’s capital — under the pretext of a skewed ‘hijab’ — has entered a fifth month. Protests started in Jina’s hometown, Seqqiz, in Eastern Kurdistan (Rojhilat) and shortly spread all across Iran after her funeral procession. Anguish has been transformed into a sustained uprising.

On the streets and campuses, protesters chant, “Jin, Jiyan, Azadî.” It literally means “woman, life, freedom,” but the scope is broader, and the impact strikes much deeper. Thus the slogan’s genesis is best preserved untranslated. As a motto, its roots trace to the Kurdish women’s liberation movement in Northern Kurdistan against the Turkish state in the early 1980s, later mentioned and interpreted in the writings of Abdulla Ocalan, the Kurdish leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) imprisoned in Turkey. The bedrock foundation of Jin, Jiyan, Azadî underlies the people of Eastern Kurdistan; There, women and men have long stood equally alongside as manifested in female organizations established in the twentieth century by Kurdish parties there, including the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran (KDP-I) and the Society of Revolutionary Toilers of Iranian Kurdistan (known as Komala). Other Kurdish parties followed suit. Women have exercised a decisive role in Kurdish movements over the last century.

In Rojava, the Kurdish self-ruled area in Western Kurdistan, the female military force (Yekîneyên Parastina Jin, YPJ) and other female parties across Kurdistan have voiced this slogan. Rojava’s self-rule has mobilized reserves of latent power, instilling a different form of self-determination, renouncing the nation-state system to promote democracy, pluralism, women’s empowerment, ecology, and self-defense (the Social Contract of Rojava). But Jin, Jiyan, Azadî transcend the hijab — which is not a primary issue for the Kurds but a defining fetish of the Iranian regime. The slogan means free life is unachievable without women’s freedom and without eliminating discrimination and societal inequalities. Self-determination has been a prime Kurdish concern for the Kurds, who have been deprived of its exercise over the whole century since the World War I armistice.

In the early 20th century, the political future of Kurdistan and that of the Kurdish nation were at stake as the Allies pursued their own interests in prescribing national rights to self-determination following World War I (WWI). The Kurds were promised the right to local autonomy and then independence within one year by the Treaty of Sèvres (1920). But then, in a betrayal of that treaty and despite major nationalist movements, the Kurds of Eastern Kurdistan were excluded from self-determination. Britain opted instead to respect the territorial integrity of Persia (later Iran in 1936) under the Anglo-Persian treaty of 9 August 1919. The signatory states never implemented the Sèvres Treaty. It was eventually reversed by the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), studiously ignoring the Kurds and thus forestalling the emergence of Kurdistan as a state. The Kurds were thereupon divided among the states of Turkey, Iran, Syria, Iraq, and Soviet Armenia. Later and with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the regional Kurdish minorities in Soviet territories were split between the separate Republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan. Many Kurds had earlier been deported to other Soviet republics. Thus Kurdistan came to be a contiguous ethnic region, arbitrarily divided across only four states. The Allied Powers’ political and economic interests, especially those of Britain, France, and the Soviet successor state to Russia, had a decisive role in the Kurds’ failure to achieve territorial independence (i.e., sovereign statehood). Kurds are now considered a territorially fragmented people, the legacy of a policy prescribed from outside the region by the Allies of WWI.

The Republic of Kurdistan, established by the Kurds of Eastern Kurdistan, experienced an aborted lifespan in 1946, terminated when its leaders were executed by the Pahlavi royal regime in Tehran. The assassination of Kurdish leaders continued a serial crime committed by both Shah’s government and extended to the heart of Europe after 1979 by the ayatollahs’ regime. Some Kurdish representatives were murdered even as they awaited the arrival of Iranian negotiators. Cases in point include the deceitful murder of Kurdish leaders: Simko Shikak, the execution of Qazi Muhammad and his fellows, Foad Mostafa Soltani, the assassinations of Dr. Qasimlu, Sediq Kamangar, Dr. Sadeq Sharafkandi, and many other activists inside Eastern Kurdistan or based in Southern Kurdistan.

The systematic, extrajudicial killings and the excessive use of force against the Kurds are noted in human rights reports. Furthermore, almost all UN reports on the human rights situation in Iran have commonly recorded violations of Kurds’ economic, social, and cultural rights. A disproportionately significant number of Kurdish political prisoners receive the death sentence and have thus far been put to death. Human rights breaches constitute the daily essence of Tehran’s domination.

In terms of ethnicity and religion, the regime has consistently otherized the Kurds through discriminatory policies of subordination. In Eastern Kurdistan, colonization is manifested internally. Despite the regime’s assertions that it opposes colonialism and imperialism, it remains a non-self-governing territory. To implement internal economic colonialism, Tehran has disregarded the development of the poverty-stricken Kurdish regions; despite being rich in natural resources, including oil and gold, Eastern Kurdistan is plagued by the highest unemployment rates in Iran while the capital earned from its resources is diverted out of the region to the benefit of the ayatollahs’ regime. Militarization and restrictions on Kurdish life are applied as an alternative to investment and remain the essential ingredients of the regime’s presence.

The Kurds of Eastern Kurdistan, as a minority people, should now be considered candidates for implementing their right to self-determination. They are now actively renewing the fight for self-determination and world recognition as a nation. Since the outset of the uprising, several general strikes have been organized, renewing tactics used by oppressed people since 1979 to resist the Iranian regime’s violation of their political, social, and cultural rights.

According to the Hengaw Organization for Human Rights, 127 Kurds have been murdered, and more than 8000 injuries have been reported since 16 September 2022. In the ongoing mass arrests, more than 6500 people, including women and adolescents, have been jailed so far, their fate at serious risk. Among them are women and adolescents. Some of them have been sentenced to death on the charge of “enmity against god” or muharebeh (“war against God”). In addition, more than 300 juvenile students have been kidnapped. Systematic sexual violence has been deployed by the Iranian authorities against most prisoners. Lethal, unabated suppression is also underway by the Iranian regime’s forces in the city of Sne (or its colonial name Sanandaj) and Mahabad through militarization, heavy weaponry, and electricity blackouts at night. For months, many Kurdish cities have endured a vicious crackdown. What is happening is reminiscent of the state-sponsored massacre and extrajudicial executions of the Kurds after the “Islamic Revolution” in 1979. Other Kurdish cities have not been spared violent repression. Awdanan, Ilam, Kirmashan, Piranshar, Degolan, Pawe, Jwanro, Sardasht, Bokan, Diwandara, and Kamyaran are worth mentioning. A field report proves that the banned gas CS has been used in Jwanro against people returning from a funeral procession, and heavy caliber bullets have killed many. This massacre is intentional, an act committed with the intention to destroy — a significant element of genocide in international law — the Kurdish nation. It is noteworthy that the situation in Baluchistan is even worse, with more than 120 killed primarily on a single day. Thus, the deadly burden of the freedom movement has been borne primarily on the country’s national and ethnic geographic margins as it has been so since 1979. These cases should be investigated, and all involved should be subject to judicial accountability.

Unable to quell the uprising, the regime’s retaliation, as always, is to strike at the Kurdish opposition parties’ headquarters based in Southern Kurdistan (in Iraq) for the third time with suicide drones and missiles, which has already led to the killing of 20, among them a pregnant woman and her infant, and more than 50 injuries. This violation of sovereignty is meant to blame the uprising on external Kurdish parties as if the massive outrage at their oppressive policies within Iran needed outside incitement. The regime must be blamed for its cynical denial policy on a distinct nation within its political boundaries and the systematic, extrajudicial killings and excessive use of force against the Kurds.

By international standards, Tehran has long since forfeited its legitimacy in Eastern Kurdistan. Both the previous and incumbent governments have trampled on the Kurds’ political, social and cultural rights. In addition to being denied any political power, the Kurds there had no part in putting these governments in place. Boycotting the 1979 referendum for a new constitution was a prominent instance of their resistance facing a new regime committed to denying the Kurds’ rights. Tehran’s government has never included representation by Kurdish-affiliated ministers. What forms Kurdish self-determination in Eastern Kurdistan takes must depend not on outsiders but on the Kurds themselves. This will not be possible without the Iranian regime’s loss of its effective control over Eastern Kurdistan. Given these realities, the uprising necessarily takes the aspects of a ‘revolution’. The indications of a revolution have already been evident that might give rise to the overthrow of Ayatollah’s theocratic dictatorship.

The Kurdistani segments (North, South, East, and Rojava) across four states have been the epicenter of significant progressive developments in the Middle East over the last decades. With Jin, Jiyan, Azadî as the echoing call, self-determination can be achieved to empower distinct, modern, forward-looking people. This outcome could serve as the catalyst leading to a more peaceful region. And this slogan resounding worldwide, may yet inspire other peoples to throw off oppressive regimes.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here represent those of the author and not necessarily those of the WKI.