Washington Kurdish Institute

October 15, 2020

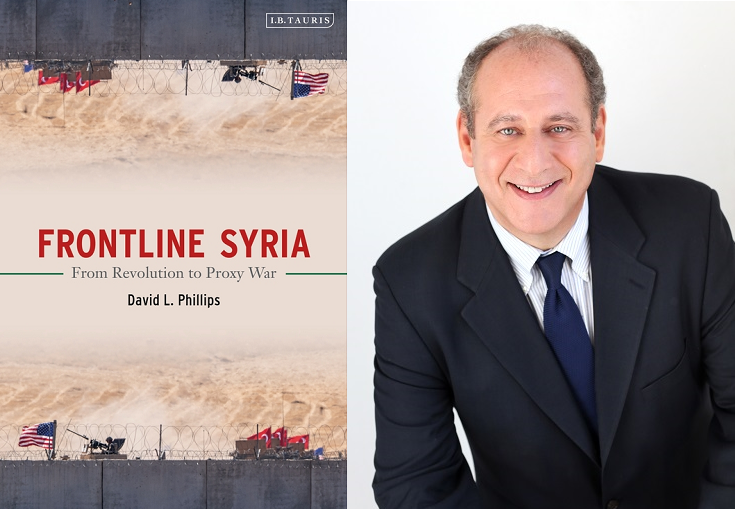

The Washington Kurdish Institute (WKI) interview Professor David L. Phillips, the Director of the Program on Peace-building and Rights at Columbia University’s Institute for the Study of Human Rights. Professor Phillips spoke about his recent publication, Frontline Syria- From Revolution to Proxy War and the Syria civil war.

About Frontline Syria

When the Syrian regime used sarin and other chemical weapons against dissidents in August 2013, an estimated 1729 people were killed including 400 children. President Barack Obama warned that the use of chemical weapons would constitute a “red line”, but he refused to take military action. Trump’s approach has been even more disengaged and lacking in clarity.

Frontline Syria highlights America’s failure to prevent conflict escalation in Syria. Based on interviews with US officials involved in Syria policy, as well as UN personnel, the book draws conclusions about America’s role in world affairs and its potential to prevent deadly conflict. It also highlights the role of front-line states in Syria and other countries who engaged in the Syrian conflict to advance their national interests.

Purchase link: www.bloomsbury.com/us/frontline-sy…-9780755602568/

Interview Summary

Interview

Why did you decide to write the book now, nearly a decade after the war began?

Syria won’t be the last time that the US is challenged to address genocide and to work with allies and multilateral institutions to promote peace and do peacebuilding. We’ve made so many mistakes in Syria from the beginning, from March, 2011 to the present. I thought it was important that we document those mistakes. And of course, there’s plenty of blame to go around. The Obama administration made mistakes of its own, but I wanted to highlight the egregious errors of judgment and the immoral leadership of the Trump administration, which made a bad situation worse. The book describes how the US failed Syria, and it shines a light on the Trump administration’s failures in particular, as of late.

What opportunities did the US have to intervene in Syria, either diplomatically or otherwise?

There’s a long list of them from the incident in Daraa in March of 2011, when the teenagers were painting graffiti on their school wall. The US should have issued public statements that were strong, condemning Assad’s behavior and expressing solidarity with the people of Syria. That would have been consistent with the broader goals of the Arab Spring. The UN security council endorsed the Annan six point plan in March of 2012, but there’s much more that we could have done to give implementation more traction and to support it, not just rhetorically, but materially. In August of 2013, when chemical weapons were used in Ghouta, President Obama said it was a red line, but we never enforced the red line. He later said it was a warning rather than a threat, but when more than a thousand people, including hundreds of children were killed using Sarin and other chemical weapons, the US should have reacted with more than just words. Beginning in 2014, there was a debate going on in Washington about supporting the Free Syrian Army through a train and equip program. The US suffered from paralysis through analysis. We feared that by giving weapons to the FSA, they might eventually use those weapons against us. So instead we sent rations and ready-to-eat meals. We didn’t send bombs and other offensive weapons, which is what they really needed. And then of course, we initially failed to respond to ISIS and Turkey’s aggression in Kobani. The US was unwilling to make a firm and ongoing commitment to the People’s Protection Units. We treated them like foot soldiers, instead of as allies with whom the US shares values. Failure to work more closely wth the Kurds was a a strategic mistake.

How did the involvement of other foreign countries such as Russia, Turkey, or Iran contribute to the bloodshed in Syria?

There was a vacuum. Without the US filling the vacuum, a space was created for Vladimir Putin to come to the UN Security Council where he clear that Russia’s interests lay with the regime. Absent a more robust role for the US, Russia was enabled to provide diplomatic and material support to Damascus. That also opened the door for Iran. Had the US been more proactive, had we demonstrated a stronger commitment to the Syrian people, we wouldn’t have opened the space for Russia to come in. And as we’ve seen, not only in Syria, but elsewhere, Russia is a bad actor. Their policies are antithetical to human rights. Russia is looking to confront the US wherever possible. The Astana process that included Russia, Iran, and Turkey proved to be a diplomatic fiasco, undermining the UN initiative. Without proactive leadership and engagement by the US, it created opportunities for other actors to come in and they did so to the detriment of the Syrian people.

Do you believe that if the Kurds had asked for diplomatic recognition or anything else in return in this sort of quid pro quo idea that you just proposed, do you think that Washington would have actually given them something at the time?

Well, let’s look at both Iraq and Syria to answer your question. The time of maximum leverage for the Kurds in Iraq was before the Battle for Mosul. Instead of waiting until ISIS was defeated, The Kurdistan Regional Government should have made very clear that it wanted the US to revise its One Iraq policy and ultimately to support a popular referendum on independence. The same thing can be said for the Syrian Kurds. They should have made their needs crystal clear. You don’t wait until the end of the battle to start negotiating your payback for fighting on the front line. You initiate those discussions at the beginning, when you have maximum leverage. With hindsight, we don’t know what the Trump administration would have done in Syria, but we do know that the Syrian Kurds trusted Washington, they trusted Donald Trump, and that trust was misplaced.