Washington Kurdish Institute

By: Colin Tait, February 3, 2020

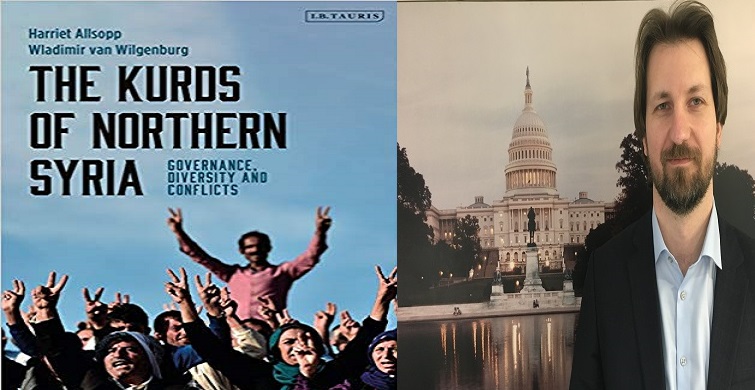

Today we’re talking with Wladimir van Wilgenburg on his latest book, the Kurds of Northern Syria: Governance, Diversity and Conflicts. Wladimir van Wilgenburg is an analyst of the Middle East, with a particular focus on Kurdish issues. Wladimir has closely covered key events on the ground, including the battles with the Islamic State in Raqqa and Baghouz Fawqani. He is the co-author of the recently published book The Kurds of Northern Syria: Governance, Diversity and Conflicts. His book provides a nuanced assessment of the Kurdish autonomous experience and prospects for self-rule in northeast Syria. It is the first English-language book to capture the transformations that have occurred since the start of the civil war in 2011. Wladimir had unprecedented access to northeast Syria and conducted momentous field work to encapsulate the evolution of self-rule in Rojava.

Colin Tait (CT): Thank you so much Wladimir for this opportunity to interview you about your new book. What inspired you to conduct this research and write the book? Can you discuss your research methods?

Wladimir van Wilgenburg (WW): It was not my own idea. I was approached by Dr. Faleh Jabar and he had a project for the Iraq Institute for Strategic Studies to do a research project, not on the Kurds only of Syria, but also of Iran, Turkey, and Iraq. So, all the parts of Kurdistan, let’s say. Me and [co-author] Dr. Harriet Allsopp, we did the research together and the book is focused not only on the field research, interviews, but also a number of surveys. We did around 180 surveys. The idea of the project was to have a sort of standard book so that you have a book on all these Kurds from these different parts of Kurdistan. And that’s how it all started basically. Then, in 2016 I did several months of research on the ground. But because of the difficult conditions, sadly Dr. Faleh Jabar passed away in 2018 and also because of the developments on the ground that took some time for that. The book was published in 2019.

CT: What is the current state of the union in the Autonomous Administration? And what does the governance structure look like?

WW: I mean the government structure is very different if you compare it, for instance, to Iraqi Kurdistan where you have the Kurdistan Regional Government because in northeastern Syria, this is not just the Kurdish areas they control. You have, of course, Rojava, Syrian Kurdistan, but they also control areas like Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor. So, the Administration is not based on, for instance, a Kurdistani identity, the identity is multi-ethnic. It’s a combination. That’s why the Administration logo, it’s in four languages. And that’s why the situation is a little bit different than, for instance, for the Iraqi Kurds, because the Syrian Kurdish led Administration, they fought also in our Arab majority cities. For instance, in Iraq the Peshmerga didn’t really fight inside the city of Mosul but in Syria, it’s very different.

CT: How have Kurdish politics in Syria evolved since the civil war started in 2011? What are the notable successes and failures throughout the development of the PYD (Democratic Union Party) led project of self-rule?

WW: Well, the Syrian Kurdish parties, in the beginning, they attempted to establish a united sort of Administration. So, on one hand, you had the Kurdish National Council, and on the other hand you had the Democratic Union Party. Between 2012 and 2014 there were attempts to reach sort of a unity agreement, but this never worked. And as a result, they didn’t have, for instance, a similar social contract that you have in Iraqi Kurdistan where the Kurdish parties agreed on forming a government together. They didn’t have that. But despite of that they have been very successful in creating an Administration because in the end they controlled over 30% of northeastern Syria. Of course, recently they had setbacks because of Turkish operations, but in general, they managed to create, out of nothing, the whole Administration. And for instance, they managed to have an Administration with thousands of employees and they’re selling oil. So, in a short period of time between 2014 when they first announced the Administration, until now, they have managed to build like a huge Administration system. But there’s also things that can be improved. It would have been better if they could have held elections because until now, most of the councils and the Administration bodies, they’re appointed representatives from their own community. But in this kind of civil war, it’s difficult to do a democratic election. You have the Syrian civil war. I mean, they’re still fighting against ISIS. There are still challenges from the Syrian regime or attacks by Turkey. You cannot compare it to, for instance, the situation will Iraqi Kurdistan where they had the no-fly zone and there was not really a big threat at that point from Saddam Hussein. But then in the end, they had their own internal differences in Iraqi Kurdistan. So, I think they could have maybe done elections, but at the same time, I’m not sure if you can blame them for not implementing a fully electoral system yet because there also are a lot of challenges like attacks from different actors.

CT: Focusing specifically on Turkey, how did the October invasion of last year affect the Autonomous Administration?

WW: Well, what’s interesting to see that at the same time a lot of things have changed, but at the same time things have not changed so much. So, Turkey, they control a limited border strip, which is completely isolated and surrounded by the SDF and the Administration is still working in northeastern Syria. So, they’re still able to pay the salaries and so far, there have been no major defections from the Kurdish-led forces from the Syrian Democratic Forces. And the situation is somehow still stable. But the fear is that in the future, there could be another Turkish attack. Although in that case, U S says they’re going to put huge sanctions chances on [Turkey]. There is still an attempt to reach an agreement with the Syrian government, and this is still not working well. So, the fear is that there’s going to be in the future, either more pressure from Turkey or from the Syrian regime, but until now, even though that in October, Syrian government forces came to prevent the Turkish expansion, the Administration has not changed. So, as a foreigner, you can go all the way to the city of Manbij, where you don’t have regime checkpoints that arrest people. There is no regime education system in the Kurdish areas. There are no people that are being stopped and arrested by the Mahabharata of the Syrian regime. So far, the Administration has stayed intact, but they lost some territory. And the fear is that in the future, Russia could put more pressure on them to surrender to the Syrian regime. While until now also, Damascus is very much focused on the battle in Idlib. So, it also is very much related to developments elsewhere in Syria and what is going to happen with the future of this Administration.

CT: I think it was last week or the week before, the Rojava Information Center released the budget of the Administration and their economy seems to be doing well. Can you discuss the factors that contribute to the success of the economy?

WW: Well, I remember before 2014, the Administration didn’t have a budget, but what they successfully did is that they started to control a large amount of the oil through the battles against ISIS. I mean, Ramalan was already controlled before they defeated [ISIS]. There was basically an attempt by Turkish-backed groups to control Ramalan. This was like much earlier around 2012 – 2013, but then after the battle of Del ez-Zor they also controlled major oil and gas fields in Deir ez-Zor. So that made the Administration possible for Administration basically to sell the oil. Some of the oil is going to the Kurdistan Regional Government and some of the oil is going to the Syrian government still. With this money they have a budget to basically pay their employees. And another contributing factor is also that the US was paying some salaries of the fighters of the Syrian Democratic Forces. They are also providing some financial assistance for mostly fighters, not for the Administration. I think this made it possible for the Administration to actually pay their employees. And this is also why that until now, although there has been a bad economic situation in the rest of Syria, there’s a lot of problems for the Syrian pound as it has crashed. There is also neighboring Lebanon where there is a lot of economic problems and protests. In general, the areas of the regime have many difficulties. For instance, with [the lack of] cooking gas and fuel for cars. But in general, the Administration has even been able to increase the salaries for the employees to deal with the rising inflation and the increasing high prices for food products. And they also banned exports of meat to the Kurdistan region and they are importing other products so that they can sell them for a cheaper price to the local population. I think that although some people say that governance wise, they were not so successful while on the military side, they were very successful. I think that’s not true. I mean they could have been more inclusive, but in general, the Administration has been quite successful in being such a big Administration, like so many employees, despite of all these challenges.

CT: The Faysh Khabur border crossing seems to be one of the lifelines of the Administration and Rojava. Do you see any imminent threats to whether the border will be open or continue to be open?

WW: There seems to be some attempts by Russia and the Syrian regime to check if they can probe the Americans to see if they can find a way to that border. But according to the official agreement between the regime and the SDF, the regime is not supposed to go to the Iraqi-Syrian border. But, also there is still a fear that Turkey could attack the small town of Kahtanieh and then make up a small corridor towards Abira that will cut off the border access because they will not control the border, but there will be no way to go around this area because it will be cut off. So far, the situation is stable. There are still threats of a possible Turkish attack, but Turkey also knows if they do an attack, there will be heavy repercussions because there’s a lot of support in the US Congress and the Senate for the Kurds in Syria. It seems the situation could stay the same. But I talked to SDF leader Mazloum Kobani and he also said, despite of everything, we should not rely on the situation. There is still a possibility that there could be an attack in Jazeera and Kahtanieh.

CT: And you discussed the inability for the Administration to be completely inclusive. Could you talk about the attitude the Arab tribes have?

WW: Well, I mean, as I said, the issue of inclusivity could be improved, but also the problem is if you look to the rest of Syria, if you compare the self-Administration to a piece of Syria [controlled by] the Syrian regime, which has killed thousands of people, not only by airstrikes but also in prisons. And if you look to the Turkish-backed groups, they have done major looting and kidnapping people for ransom. If you compare the self-Administration to the regime and Turkey including tribes, I think the SDF has been much more successful. This is not only me saying that, there’s also other research that talks about this, that basically the SDF has been more successful of let’s say coaptation of the tribes. So although some of the tribal leaders are still supported by Damascus, you’ve seen that the tribes that are still inside on the ground and the SDF maybe for various reasons, maybe they are not completely supportive of the SDF, but in Deir ez-Zor they don’t really like the Syrian regime. They prefer SDF over the Syrian regime. Also, in Raqqa, there have been challenges, but at the same time, the situation is still stable. I think this also depends on the region, but I think they have still been quite successful because even ISIS was not able to control Deir ez-Zor because all the tribes wanted to have a piece of the oil income. There were some protests in the past against the SDF because of the high fuel prices because the people are complaining why are we going to get car fuel here? It’s more expensive in Deir ez-Zor, while we have all this oil, but it is more expensive, for instance, than in Hasakah, but now I think they evened out those prices. I think in general it doesn’t mean that the Arab tribes necessarily support the system, but despite of that they have been sort of successful in including certain tribal leaders, for instance, the councils of Deir ez-Zor, in Raqqa, and also in Manbij. They have had a working relationship with these tribes. But if this Administration survives in the future and will get more recognition than it will be much more possible to get a better inclusive system because then if they have recognition, they can also have local elections. But now with all these challenges, it’s much more difficult.

CT: What other ways can the Administration improve their governance structure? I know you’ve talked several times about the inclusiveness and the inability for them to move forward with it because of all these threats. But what else can they improve on?

WW: They can improve by interacting with other Kurdish [entities]. There is now attempts by the SDF leader, Mazloum Kobani to reach a better agreement, for instance, with the British National Council. There are attempts to bring a better Kurdish unity. Also, the Syrian Democratic Council, they are organizing a dialogue. They have two Syrian dialogues. They have done this in several countries. Even people that participate in these meetings, they can criticize the Administration for their shortcomings. So what they’re trying to do is to try to bring even more people that are maybe not 100% supportive of the Administration about and maybe interested in seeing if there is space for them in this Administration to bring them together and to create an internal Syrian opposition. One of the problems I think, it’s not just because of the inclusivity of the Administration. Because if you look to the regime or the Turkish-backed groups, they’re not inclusive at all. And they don’t even care if they’re inclusive because they don’t have support of the US-led coalition. It’s just because that the SDF and the Kurds, and the Administration, they have support from the US-led coalition that there’s so much focus on [inclusivity]. But if it was the Syrian regime or if it was the Turkish backing them, there would not be this focus on inclusivity. But I think that’s why it’s also more difficult to be more inclusive because you have, the Syrian opposition that basically supports the Turkish invasion. And then you have tribes with the Syrian regime that also support the dictatorship of the Syrian regime. So I think that’s, that’s the challenge, but maybe through more intra-Kurdish dialogue and more intra-Syrian dialogue, and if they are able to continue to pay the salaries of their employees and also give more positions to certain people from Arab backgrounds, and try to improve the economic situation, not only in the Kurdish towns, but also in Deir ez-Zor. And I think it will, it will be able to improve it much better. But I think so far, they have not neglected the Arab areas. Sometimes Kurds will complain, why does all this humanitarian support go to Raqqa or Deir ez-Ezor. I think the main challenge is what’s going to happen with the Syrian regime and Russia.

CT: I know it’s hard to predict the future as it depends on a lot of the various factors that you talked about today. But are you optimistic, optimistic for the future of the Autonomous Administration? What do you see in possibly five years in northeastern Syria?

WW: I think in the short term, unless Turkey attacks, I think the Administration has a good, status quo, if the U S stays and the state situation stays like this. Then I think they have good prospects. But I think the main challenge is what’s going to happen after Idlib and if they will focus more on northeast of Syria. I was more optimistic about the future of the northeast of Syria when there was just US forces there to be very honest. I mean they still have prospects. I’m not saying that it’s going to be necessarily a negative scenario because it’s still very much out in the open. Like nobody exactly knows what’s going to happen. But I think there will be much more challenges for the Administration and the Syrian Democratic Forces now that the US has reduced its presence.

CT: What comes next for you? Do you have any upcoming projects or any current projects that you’re working on?

WW: Well, I mean I’m still working on several projects. I’m still doing research on the SDF for a paper. I am also in general writing articles about the situation in the northeast of Syria. I am also looking for possibilities of maybe publishing a new book on Kurds, but so far that’s unclear. I keep following the current situation in Rojava in northeast Syria, but also in other parts of Kurdistan, like the Kurdistan Regional of Iraq, the Kurds in Turkey and the southeast of Turkey or North Kurdistan, and the situation of the Iranian Kurds of Rojhelat. So, I keep doing news reports, but also bigger think-tank reports.

CT: Good luck with everything and thank you so much. I’m very excited to read your book.

WW: I hope you enjoy it.

Music by: Abdullah Jamal Sagirma