Washington Kurdish Institute

September 5, 2017

On August 29, Kirkuk’s Provincial Council (KPC) voted in favor of the province participating in the upcoming referendum for independence along with the Kurdistan region of Iraq on September 25, 2017. Both the Turkey-backed Iraqi Turkmen Front bloc and the Arab Coalition in the KPC boycotted this vote, though the Kurdish-majority Brotherhood bloc supported this measure, and it ultimately passed with the support of some non-Kurdish representatives. The decision to join the referendum by the KPC came after Kirkuk Governor Najmaldin Karim wrote a letter suggesting this measure. Kirkuk will now prepare for the referendum despite strong objections by regional powers and the United States against the process. These objections are not only against Kirkuk’s participation, but rather against the whole process of conducting a referendum for independence in the Kurdistan region of Iraq.

Immediately following the KPC’s decision, the Turkish Foreign Ministry released a statement describing the vote as “serious breach”. Turkey’s position on the referendum is neither new nor surprising, as they made their strong opposition known in the past on several occasions. Turkey also opposes any type of independence for Kurds and even opposes federalism for the Kurds in Syria and Iran over fears that the Kurds living within Turkey’s borders (who outnumber the Kurds of Iraq, Iran, or Syria) will demand the same status as they continue their struggle for human, cultural, and political rights that has been ongoing since the creation of Turkey. Iran also opposed the KPC’s decision, describing it as “provocative and unacceptable.” Iraq’s Prime Minister also voiced his “rejection” of the decision. The positions expressed by Iran, Iraq, and Turkey correspond with the U.S. administration’s policies as well.

Despite their strong objections to Kirkuk’s participation in the referendum, the process will not determine the province’s future. Iraq’s constitution contains an agreed solution, Article 140, for determining the status of the disputed territories, i.e., those areas claimed by the Kurdish people of Iraq which remain outside the borders of the region currently administered by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), including Kirkuk. Due to its wealth of oil and gas resources, the Kirkuk province is the most hotly disputed area, though historically it has always had a Kurdish majority, despite forced demographic changes brutally perpetrated by previous Iraqi regimes. To date, the Iraqi government has failed to implement Article 140 of the constitution, repeatedly delaying to address the issue of Kirkuk since 2005. The Iraqi government has also prevented Kirkuk from holding provincial elections since 2005 under the pretext of auditing voter registration, though the very same registration process in Kirkuk has been deemed valid for previous general (parliamentary) elections. These contradictory policies have greatly contributed to a loss trust between Kirkuk to Baghdad. Moreover, the Iraqi government stopped providing Kirkuk with its federal budget allocation and oil share since 2013, exacerbating and perpetuating a grave ongoing economic crisis. Iraq’s army fled Kirkuk when the ISIS terror group moved toward the area in 2014 and surrendered 40% of the Kirkuk province (the Hawija district) to ISIS in 2014, which create massive displacement in the province. Since June 2014, Kirkuk has been hosting half a million internally displaced persons (IDP) without any significant aid from Baghdad. Today many of the IDP’s home areas have been liberated from the control of ISIS, but a shortage of basic services and actions of sectarian militias prevent their return. The KPC’s decision makes sense not only for the Kurds, who seek to join historically Kurdish Kirkuk to the Kurdistan region, but also to non-Kurdish citizens that have endured Baghdad’s malevolent policies of neglect with respect to Kirkuk.

KIRKUK

A key feature of Kirkuk is its diversity – Kurds, Arabs, Turkmens, Shi’ites, Sunnis, and Christians (Chaldeans and Assyrians) all co-exist in Kirkuk, and the province is even home to a small Armenian Christian population.

GEOGRAPHY

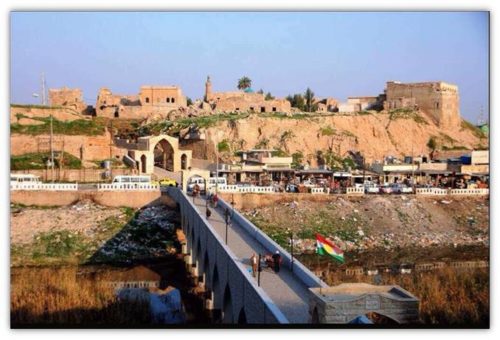

The province of Kirkuk has a population of more than 1.4 million, the overwhelming majority of whom live in Kirkuk city. Kirkuk city is 160 miles north of Baghdad and just 60 miles from Erbil, the capital of the Iraqi Kurdistan region. Since the creation of the state of Iraq, Kirkuk has been an important connection between the north and the south via Iraq’s highway 2.

ECONOMY

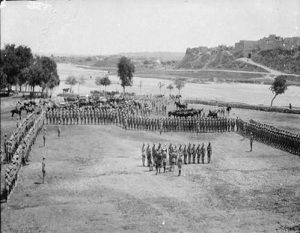

Kirkuk is often called the city of the black gold, because of its rich oil deposits. In fact, the first oil production in Iraq occurred at Kirkuk’s oil fields during the British occupation. According to BP (formerly British Petroleum, and before that called the Anglo-Persian Oil Company), oil was discovered in Iraq in 1927 in what would become the immense Kirkuk field, with the Baba Gurgur field at its heart. In 1939 and during World War II, all three British armed services used oil and lubricating equipment from BP heritage company Castrol, which utilized Kirkuk oil, and the British air force depended on that oil. More recently, during the Iraq-Iran war from 1980-1988, Saddam’s regime heavily depended on Kirkuk’s oil to fund of the war. At the time, Kirkuk was producing about one million barrels of oil per day. Kirkuk has always been a contributor to Iraq’s economy and an important factor in the country’s wars.

Today, Kirkuk is producing around 340,00 barrels of oil per day due to damage that occurred to the fields over the past decades. The province’s oil revenue is currently shared between Baghdad and the KRG. By the end of 2011 Kirkuk’s economy was boosted after Iraq’s lawmakers passed a law granting the oil producing provinces a share of oil revenues (i.e., a dollar for each barrel produced).

In April 2011, a new governor of Kirkuk, Najmaldin Karim, a Kurd and native of Kirkuk, was elected and the Kurds agreed that the position of speaker of the provincial council would be allocated to a Turkmen representative, while an Arab representative would act as deputy governor position. The new local government built hundreds of new schools, tens of bridges, new water supply lines, large sewerage lines, and paved about 1,000 miles of new roads, and effected many other improvements to the province’s infrastructure. Most importantly, the administration addressed the issue of the electricity by signing a contract with a company to provide Kirkuk with power. The oil share revenue supported the hiring of about 6,000 local contractors to staff various departments in Kirkuk. After years of economic hardship and struggle during which Kirkuk’s resources went to fund others’ lives, the people of Kirkuk were satisfied with the direction the city was heading.

These economic developments played a large role in de-escalating political tensions in Kirkuk. In this new positive atmosphere, during the 2014 general elections, many Kurds and non-Kurds in Kirkuk voted for Kurdish governor Najmaldin Karim, who won 150,084 votes, over 110,000 more than the second most successful parliamentary candidate (Ershad Salihi of the Iraqi Turkmen Front) in the province. This was a clear indication that, after 8 years of political disputes, the people of Kirkuk cared more about basic services than political disputes.

Unfortunately, the situation in Kirkuk did not remain calm. In 2013, Baghdad stopped providing the oil share revenue to Kirkuk. In 2014, after ISIS occupied Mosul, the Salahuddin province, parts of Diyala and 40% of the province of Kirkuk (the Hawija district), approximately 600,000 IDPs fled to Kirkuk city, creating an even greater economic burden for a city that had already faced increasing troubles following Baghdad’s decision to deprive Kirkuk of its budget allocation. To this day, Kirkuk is suffering from a multifaceted economic crisis caused by Baghdad’s policies, the IDP crisis, and other effects of the war against ISIS, and there are currently about 105,000 families of IDPs in Kirkuk who are unable to return to their homes even though their native areas have been freed from ISIS.

HISTORY:

Arabization

Arabization, a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing demographic change, began in Kirkuk soon after Iraq was created as a state. In 1936, during the reign of King Ghazi bin Faisal, Iraq’s second monarch following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the Hawija project began. This project, which was completed in 1953, involved the construction of an irrigation river that covered approximately 139,000 acres of farmland. Thousands of Sunni Arab families then moved from Salahuddin and Mosul provinces to Hawija. In 1961, nine years after the project was completed, the Iraqi government created the Hawija district and incorporated it into the Kirkuk province, adding a new district to the province with an Arab majority population.

In the 1970s, an official program of Arabization of Kirkuk took place in which Kurds were displaced from the province and replaced by Arabs. The Iraqi regime offered Arab families 10,000 dinars (then $33,000) to settle in Kirkuk, along with land and a business opportunity. As part of Arabization efforts, the Iraqi government also changed the administrative borders of Kirkuk province, removing several Kurdish majority towns and districts and allocating them to other provinces.

Specific examples of geographic Arabization measures:

- On December 15, 1975, Republican Decree 608 removed the Kurdish majority Kifri district from Kirkuk, allocating it to the Diyala province. This decree also removed the Kurdish majority districts of Chamchamal and Kalar from Kirkuk and allocated them to the Sulaymaniyah Province

- On January 19, 1976, Republican Decree 41 removed the Tuz district from Kirkuk and allocated it to the Salahuddin province

- On November 16, 1987, Republican Decree 111 removed the Arab sub-district of al-Zab from the Salahuddin province and allocated it to the Hawija district of Kirkuk

How do we know that the majority of Kirkuk’s population at the time were Kurds? According to the most reliable Iraqi census, that of October 1957, the population of the Kirkuk province was 388,829, divided as follows:

- Kurds, 48%

- Arabs, 28%

- Turkmens, 21%

- Others, 3% (including Christians, Yazidis, and foreign workers)

During the Arabization of Kirkuk, Kurds could not buy any property or run businesses in their own names. In the late 1990s, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein issued a new decree called “Nationality Correction” whereby the remaining Kurds (along with Turkmens and any other non-Arabs) in Kirkuk were forced to “change” their nationality from Kurdish to Arabic in order to get hired or buy vehicles, properties, etc.

Article 140 of Iraq’s Constitution

After Operation Iraqi Freedom and the removal of the regime of Saddam Hussein and the Ba’ath Party, a new Iraqi constitution was passed after significant debate on October 15, 2005. Article 140 of the constitution calls to normalize the situation of areas that suffered from Arabization and forced change in demographics. This also occurred not only in Kirkuk but also in other areas of Iraq such as Sinjar (Shingal) and the holy city of Najaf in the south of the country.

Article 140 calls for implementation of Article 58 of the Transitional Administrative Law (TAL), Iraq’s interim constitution adopted following the fall of the Saddam regime, stating, “The executive authority shall undertake the necessary steps to complete the implementation of the requirements of all subparagraphs of Article 58 of the Transitional Administrative Law.” Article 58 of the TAL mandates that the Iraqi authorities “shall act expeditiously to take measures to remedy the injustice caused by the previous regime’s practices in altering the demographic character of certain regions, including Kirkuk, by deporting and expelling individuals from their places of residence, forcing migration in and out of the region, settling individuals alien to the region, depriving the inhabitants of work, and correcting nationality.”

This article mandates that the Iraqi central government normalize the situation in these areas and compensate the victims, and subsequently hold a referendum to determine the future of Kirkuk by its people on a “date not to exceed the 31st December of 2007.” Nearly a decade after this deadline, the referendum has yet to occur, and the Kirkuk province remains under the sole jurisdiction of the Iraqi central government, but nonetheless disputed with the KRG and, more broadly, the Kurdish people.

KIRKUK’S DYNAMIC POLITICAL MAP

The situation in Kirkuk is further complicated by the presence of numerous political players and parties within each ethnic group of the province.

The most recent local elections took place in 2005, and the Arabs partially boycotted these elections, resulting in over-representation of Kirkuk’s other groups being reflected in the results. The pretense for not holding local elections involved voter registration – Turkmen parties refuse the accept the use of the current voter registration system/database even though Kirkuk conducted general elections every four years.

The following are a number of the more major political parties in Kirkuk:

Kurdish

Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) – 6 deputies representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament

Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) – 2 deputies representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament

Change Movement (Gorran) – No deputies representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament

Kurdistan Islamic Union – No deputies representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament

Kurdistan Islamic Group (Komal) – No deputies representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament

Other small parties-No deputies representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament.

Arab

Coalition of Kirkuk Arabs – 1 deputy representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament

The Arabs’ Coalition – 1 deputy representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament

Other movements- No deputies representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament

Turkmen (Shi’ite and Sunni):

Iraqi Turkmen Front (which includes several political parties including the Turkmeneli Party and Iraqi Turkmen National Party, and Islamic Movement of Iraqi Turkmen) – 2 deputies representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament

Christian (Assyrian and Chaldean)

Assyrian Democratic Movement – 1 deputy (guaranteed by quota system) representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament (quota one deputy)

Chaldean Syriac Assyrian Popular Council-No deputies representing Kirkuk in Iraqi Parliament

Local Government

A Kurdish Governor of Kirkuk: Najmaldin Karim

An Arab Deputy Governor: Rakan Saed

Rebwar Talabani serving as acting speaker for the Kirkuk Provincial Council after the Turkmen speaker, Hasan Turan, became a member of parliament in 2014. Rebwar Talabani remains acting speaker as the Turkmen parties have been unable to come to an agreement on a nominee to replace Turan.

Provincial Council (41 Members):

- 26 Members from the Brotherhood bloc (primarily Kurdish representatives with few Non-Kurds)

- 9 Turkmen members of the Turkmen Front and Islamic Turkmen Coalition

- 6 Arab members from Iraqi Republican Gathering

SECURITY

After 2003, new local police forces were formed to protect the city. In 2006, the Iraqi army’s 12th Division assumed control of a large swath of Hawija stretching from southwest Kirkuk to the city’s airbase, and was tasked with maintaining security in the restive district.

In June 10, 2014, the 46th Brigade within the 12th Division was the first to withdraw from Kirkuk when faced with attacks from ISIS, and other brigades soon followed suit. Upon fleeing, the army and police left behind military vehicles, high quality US-supplied weapons, and other equipment. Within 24 hours of this mass desertion by the Iraqi security forces, ISIS swept in and gained full control of Hawija and its subdistricts, home to an estimated 200,000 people, and was perfectly positioned to invade and occupy Kirkuk city and its oil fields. Despite their persistent efforts, ISIS failed time and time again to advance on the strategic city because of the intervention of the Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga forces.

Kirkuk has faced periodic terrorist attacks since the fall of the Saddam regime. The most deadly ISIS attack on the city occurred on January 31, 2015 when 400-450 ISIS terrorists attacked Kirkuk but were defeated by local security forces. This incident marked the largest attack by ISIS on any city except for Mosul and Kobani. In this attack, ISIS used a number of highly trained foreign fighters along with some local fighters from Hawija.

When the Iraqi security forces abandoned Kirkuk, the Peshmerga filled this gap to protect the city. ISIS repeatedly tried to strike and control oil and gas sites in Kirkuk, which would have resulted in a humanitarian, economic and environmental disaster, but these attacks were always foiled. The Peshmerga forces were supported by the U.S.-led coalition in protecting Kirkuk from outside threats. Local police and Asayish (public security) were the chief internal security forces responsible for providing security and preventing terrorism within the city of Kirkuk. The Peshmerga battalion of the elite Counter Terrorism Group (CTG) also played a significant role alongside the regular Peshmerga forces in repelling various ISIS attacks on Kirkuk. The vigilant defense of Kirkuk did not come without a cost – repelling these ISIS attacks since June 2014 cost the lives of 463 members of the Peshmerga forces and Asayish, and the Kirkuk police lost 85 officers.

In October 2012, prior to these large ISIS incursions, former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki formed the Tiger Command, which he attempted to use to control the security situation in Kirkuk by using Iraqi army battalions in the city, similar to what was done in Mosul and Tikrit. Kirkuk’s administration and the Kurdish leadership rejected this initiative, which resulted in an escalation of tensions between the Kurds and leadership of Kirkuk, and their counterparts in Baghdad. Had Kirkuk accepted the Tiger Command, the city may well have fallen to ISIS in 2014, as did both Mosul and Tikrit.

Today Hawija remains under the control of ISIS, even as the terror group continues to lose ground elsewhere in Iraq, and the Iraqi government has yet to provide a plan for the liberation of the area.

Popular Mobilization Units (PMU)

Many of the Popular Mobilization Units elements in Tuz (part of the Salahuddin province since 1976) are backed by Iran. PMU forces are based in the Tuz district, located south of the city. The Peshmerga forces and PMU forces have clashed at least twice in Tuz. Clashes between the Peshmerga forces and PMU forces took place 6 months apart, in November 2015 and then in April 2016. The threat from Iranian-backed PMU forces remain high in Tuz, and the Kurdish parties in Kirkuk oppose any intervention by the PMU forces in the city of Kirkuk. In the Kirkuk province, there is a Turkmen PMU group based in the Taza district.

REGIONAL POWERS AND KIRKUK

Iran and Turkey are the two regional powers that strongly oppose Kirkuk joining the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, and both interfere in Kirkuk’s local politics. In March 2017, the Kirkuk Provincial Council passed legislation to raise the flag of Kurdistan alongside the Iraqi flag following the suggestion of Kirkuk’s Governor, and both Iran and Turkey expressed their disapproval. Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said, “If the flag is not lowered, a heavy price will be paid.” Turkey also provides financial support to several Turkmen parties in Iraq since 1997.

This intervention dates back at least as far as the establishment of the new post-Saddam order in Iraq. In July 2003, following the appointment of a new Kurdish governor in Kirkuk, several Turkish soldiers were detained by the U.S. Army following a raid on Turkish offices in Sulaymaniyah in Iraqi Kurdistan. These Turkish soldiers were involved in a plot to assassinate the governor of Kirkuk, and during the raid “American soldiers seized 15 kg of explosives, sniper rifles, grenades and maps of Kirkuk, with circles drawn around positions near the governor’s building” as reported The Guardian (UK).

Iran supports certain PMU groups in Tuz to destabilize the area when they desire to do so. Iran also uses their leverage over the Iraqi government to prevent the implementation of Article 140.

In the United States, there is a significant amount of knowledge concerning the situation of Kirkuk since 2003, and the White House has made statements calling on the implementation of Article 140. However, it was never a top priority for the U.S. administrations to mediate discussions in Kirkuk. In 2012, the U.S. shut down their consulate in the city, choosing to maintain their consulate in Erbil as their only diplomatic presence in northern Iraq.

Kirkuk’s Importance

Kirkuk was a major topic of discussion immediately following the fall of the Saddam regime and today, as many are considering the major issues of Iraq and the Middle East post-ISIS, it is imperative to examine the current situation in Kirkuk and discuss the future of the city and province for a number of reasons:

- A majority of disagreements and disputes between the Iraqi federal government and the KRG concern the Kirkuk province – including oil, land, security, the border of the Kurdistan Region, etc.

- To avoid Sunni-Shi’ite, Kurdish-Arab, Turkmen-Arab, and Kurdish-Turkmen tensions and even war.

- To avoid, or at least decrease, the intervention of regional powers like Iran and Turkey in Iraq, the Kirkuk issue should be solved

- Further delay in addressing the Kirkuk issue will only make the situation worse, and the only losers are the people of Kirkuk.

- Solving the Kirkuk issue will open the door to discussing other disputed territories, as Kirkuk is most disputed area.

Many parties have coveted and taken advantage of Kirkuk for their own benefit – from the Ottomans, the British, and the Saddam regime, to the current Iraqi government. The people of Kirkuk – Kurds, Arabs, Turkmens, and Christians – deserve a solution for their home. Stability in Iraq starts begins in the Kirkuk province, and achievement of a fair and just solution in Kirkuk will benefit all of Iraq and the region as a whole. Today Kirkuk enjoys a great deal of security because of the Peshmerga forces and the local police forces. However, this could change after the elimination of ISIS, as a disputed area remains disputed until an agreement is reached.