Washington Kurdisan Institute

By: Yousif Ismael & Aveen Karim March 21, 2016

In June 2014, the Islamic State (ISIS) terrorist organization completely seized control of Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city in Iraq, following a six day offensive. Stopping at Mosul, however, was not the plan for the self-proclaimed caliphate, emboldened by the decisive victory. The Iraqi security forces proved to be inadequate when faced with the threat of the extremist group, who continued to push forward, expanding their reach inside Iraq. Following the fall of Mosul, ISIS turned toward Hawija, a predominately Sunni Arab district in the Kirkuk province southwest of the city of Kirkuk.

Following Iraq’s nationwide census in 1957, which indicated that the Kurds represented a majority among the inhabitants of the Kirkuk province, the Iraqi government began a program of Arabization of Hawija with the ultimate aim of making the Kurds a minority in the province. Today the town of Hawija and its subdistricts make up 40% of the Kirkuk province. The Arabization of Kirkuk not only involved changing the demographics of the region, but also consisted of a redrawing of provincial boundaries to which resulted in a number of districts with significant Kurdish populations within Kirkuk being assigned to other provinces – Kalar and Kifri became part of Diyala, Tuz became part of Salahaddin, and Chamchamal became part of Sulaymaniyah.

In 2006, the Iraqi army’s 12th Division assumed control of a large swath of Hawija stretching from southwest Kirkuk to the city’s airbase, and was tasked with maintaining security in the restive district. One local official who fled from the al-Zab subdistrict in western Hawija following the ISIS offensive recounted that 7 members of ISIS sleeper cells in the area rose up and declared the fall of the town. “They rode through the town in two taxis, armed with AK-47s and claiming allegiance to the Islamic State, all while praising Allah,” he said.

After witnessing the rapid and bloody fall of Mosul, the declaration by ISIS in al-Zab resulted in a sudden state of chaos, and battalions of the 12th Division and police officers abandoned their posts. On June 10, 2014, the 46th Brigade within the 12th Division was the first to withdraw, and other brigades soon followed suit. Upon fleeing, the army and police left behind trucks, US-made weapons, and other equipment. Within 24 hours of the desertion by the Iraqi security forces, ISIS swept in and gained full control of Hawija and its subdistricts, home to an estimated 200,000 people, and was perfectly positioned to take control of Kirkuk city and its oil fields. Despite their best efforts, ISIS nonetheless failed time and time again to advance on the strategic city.

In 2012, Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki established a new military command center, the Tigris Operations Command, consisting of a number of divisions of the Iraqi army, to oversee the security of three provinces, Diyala, Salahaddin, and Kirkuk, replacing local security forces. Kirkuk’s administration rejected this move which imposed a federal security presence on the province in the place of local forces, intensifying tensions between Baghdad and Kirkuk. As a compromise, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) sent a brigade of Peshmerga forces to Kirkuk to balance the forces on the ground between Iraqis and Kurds in case a war broke out over control of the city.

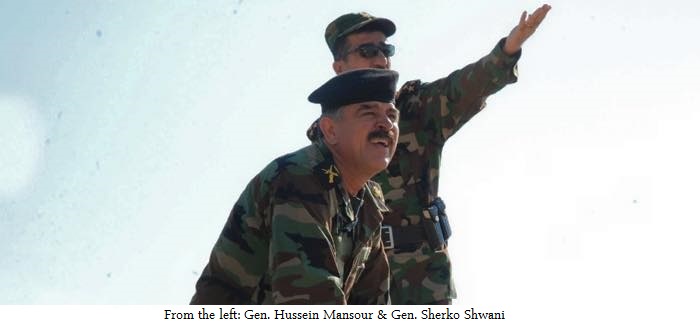

On early November 2012, the Peshmerga sent a brigade led by Peshmerga Gen. Sherko Fatih Shwani from Qara Hanjir, north of Kirkuk city, which settled outside the city facing the Iraqi army’s 12th Division. At the time, non-Kurds in the province did not see the need for a strong Peshmerga presence in Kirkuk, and Arab and Turkmen politicians expressed their disapproval of this move in the press. Some politicians even traveled to Diyala to participate in the establishment ceremony of the Tigris Operations Command in late October 2012.

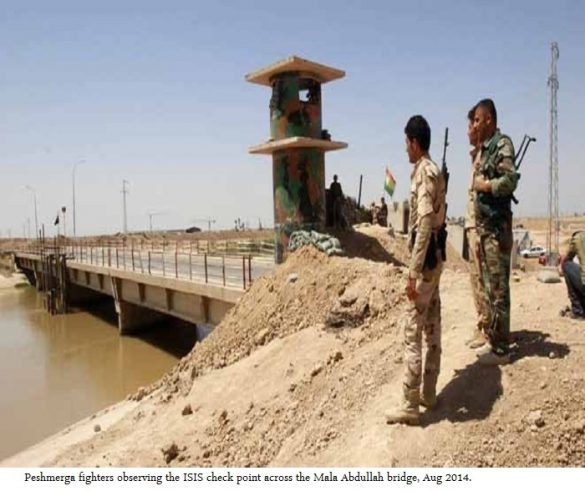

The Peshmerga began to draw borders between themselves and ISIS, and in some areas, they were only 50 meters away from one another. ISIS recruited hundreds of fighters from Hawija, increasing the threat of a potential move on Kirkuk. The Kurds never wanted to retake Hawija because it is a Sunni Arab dominated area, but they wanted to ensure that ISIS could not advance from Hawija to take control of Kirkuk. ISIS launched several offensives using both local and foreign fighters in an attempt to take Kirkuk city, but the Peshmerga defended the city and successfully repelled various waves of ISIS attacks.

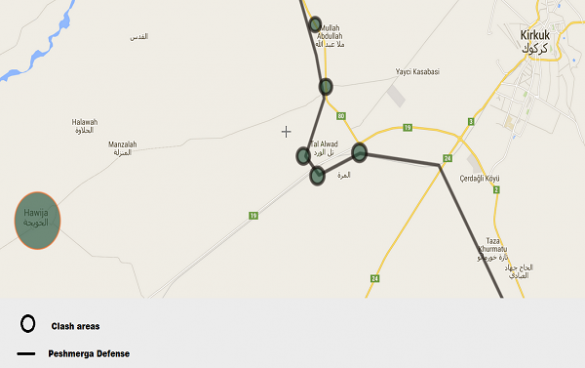

On July 17, 2014, ISIS launched an attack on Tel al-Ward, a strategic area looking over the Peshmerga’s defensive position with a direct line to Kirkuk’s oil fields. The Peshmerga brigade led by Gen. Shwani resisted the attack and stopped ISIS fighters from advancing. One Peshmerga soldier exclaimed, “We will not let them in Kirkuk.” The Peshmerga succeeded.

For months, the Peshmerga forces repelled one attack after another. Elswhere in northern Iraq, ISIS gained momentum, taking over Sinjar, Tikrit, and parts of the Diyala province. With a broadened territorial reach and a large contingent of foreign recruits, ISIS hoped to continue to expand and shift the balance of power in Iraq in their favor. In September 2014, ISIS once again attacked Tel al-Ward. With the help of US-led coalition air support and Kurdistan’s elite Counter-Terrorism Group (CTG), the Peshmerga forces stood their ground and once again defeated the ISIS offensive, killing hundreds of ISIS fighters. Unfortunately, a number of Peshmerga forces also died in battle and many more suffered serious injuries. ISIS’ campaign in Kirkuk was more challenging than their earlier moves against Mosul and Tikrit.

By November 2014, ISIS was as powerful as ever and was continuing to move to consolidate the power of their self-proclaimed caliphate. On November 26, 2014, ISIS again launched an attack against the Peshmerga at Tel al-Ward, this time utilizing heavy weapons left behind when

For ISIS, it was proving nearly impossible to penetrate the Peshmerga’s defense lines around Kirkuk, especially with the presence of air support from the US-led coalition. However, ISIS did not relent and, on January 30, 2015, the terrorist organization attempted to take advantage of the weather conditions to attack Kirkuk once again. “There was dense fog on the outskirts of Kirkuk, the visibility was 5-10 meters at the most,” said an officer from the 1st Peshmerga Brigade who participated in the January battle. This ISIS offensive was the largest in Iraq since the fall of Mosul. A CTG officer stated, “More than 700 foreign and local ISIS fighters took part in the attack, following the personal orders of [ISIS leader Abu Bakr] al-Baghdadi to capture Kirkuk.”

This attack took place across the breadth of Kirkuk’s southern frontlines in five locations. The first occurred at the Nahrwan Bridge, just a couple of miles away from the natural gas storage facility of the North Gas Company. A director at the Northern Gas Company explained, “If the gas storage facility had been blown up, it would have had the same effect as an earthquake measuring a 6 on the Richter scale, and an area of 25 square miles would have been a disaster zone.” Other Peshmerga defensive lines were Tel al-Ward, Mariam Beg, the oil fields in Mala Abdullah and Maktab Khalid, where families were fleeing from ISIS-controlled areas to cross into the city of Kirkuk. During the first 10 hours of the offensive, ISIS captured over a dozen Peshmerga soldiers and later videotaped their beheadings for use in recruitment videos.

During the attack on January 30, ISIS used a combination of truck bombs, rockets, US-made Humvees and tanks left behind when the Iraqi army fled, while the Peshmerga defended themselves with only decades old Russian-made RPGs and AK47s. A few villages were temporarily lost during the fighting, and a number of Peshmerga soldiers were killed during the battle, including 2 veteran fighters, Gen. Sherko Fatih Shwani and Gen. Hussein Mansour. Gen. Shwani was killed within the first two hours of fighting on the front lines. One Peshmerga soldier recalled, “He [Gen. Shwani] was with us fighting but was injured when the terrorists threw grenades at us and shot at close range.” Gen. Shwani and his three guards, who were also killed, fought until the last seconds of their lives.

On January 31, 2015, Peshmerga and CTG soldiers and PKK guerrillas, with the support of coalition air strikes, staged another counter assault to retake the villages they had lost. During this counterassault, Gen. Hussein Mansour, who earlier played a major role in liberating Jalawla from ISIS control, was fatally shot by a sniper while operating a heavy machine gun.

By the conclusion of the January 31 counter assault, over 400 ISIS fighters were killed, while the rest retreated back to the town of Hawija, which remained an ISIS stronghold. ISIS had never lost that many fighters in one battle in Iraq. “We received the bodies of 220 terrorists,” said a doctor who works at the morgue in Kirkuk’s Azadi General Hospital. The January battle was a turning point for ISIS, who realized that, despite their best efforts, they were never going to capture Kirkuk.

From that point on, rather than staging another large assault, ISIS would randomly fire mortars and rockets at Peshmerga positions around Kirkuk. In the spring of 2015, the Peshmerga planned to go on the offensive for the first time and take areas that had been under ISIS control since June 2014. On March 8, 2015, Peshmerga forces, backed by coalition air support, liberated all the villages surrounding the city. This ultimately eliminated a serious threat, putting oil fields and gas storage facilities out of the range of mortars and rockets. 22 villages near the Daquq and Taza sub-districts were liberated, and the offensive also cleared the Kirkuk-Baghdad road, where ISIS terrorists previously held positions only 200 meters away from the main road. By August 2015, Peshmerga soldiers and PKK guerrillas liberated another 11 villages south of Daquq, cutting off the supply lines from Hawija to their fighters. Many Peshmerga soldiers lost their lives not during the actual battle, but due to booby traps and improvised explosive devices left behind.

The Peshmerga forces received praise from all of Kirkuk’s various ethnic groups. Arabs, Turkmens, Christians, and Kurds saw that, after the collapse of the Iraqi army, the Peshmerga were the only fighting force left to defend Kirkuk’s citizens. Near the Taza subdistrict, Turkmen villagers were often seen supporting Peshmerga by supplying them with water tankers and food. Najat Hussein, a Turkmen member of Kirkuk’s provincial council, said, “If not for the sacrifices of the Peshmerga in Kirkuk, we would have found ourselves in the same situation as the people of Mosul, Salahaddin, and Anbar.” Hussein added, “On June 10, 2014, we saw the destruction ISIS caused and the collapse of four divisions of the Iraqi army. Meanwhile, we saw the Peshmerga forces fill the gap with only a small number of troops.”

Sheikh Burhan al-Asi, an Arab member of Kirkuk’s provincial council stated, “Despite the political disagreements between us Arabs and some of the Kurdish parties, we think the Peshmerga had an integral role in defending Kirkuk city.” Marwan al-Ani, an independent journalist, focused on the spread of terrorist groups, and said, “Peshmerga presence in Kirkuk saved us from the advance of the ISIS terrorists, and during the absence of any federal security forces, the Peshmerga were able to secure Kirkuk’s borders and prevent ISIS fighters from penetrating them.”

For the Kurds, Kirkuk is considered a Kurdish area outside the administration of KRG, while Arabs consider it Iraqi land. The Iraqi constitution defines Kirkuk as a disputed area as addressed in Article 140, which calls for a normalization of the demographics of Kirkuk and other disputed areas and for a referendum to determine the will of the citizens of these areas. Article 140 was supposed to be implemented nearly a decade ago, though, for political reasons, it remains pending.

More than 120 Peshmerga fighters have been martyred and more than 200 wounded on Kirkuk’s frontlines alone. They are protecting “mini-Iraq,” as some call Kirkuk, since it is composed of different ethnicities, religious groups, and sects. After witnessing how the Peshmerga forces stepped in and defeated a serious existential threat to the city, Kirkuk’s citizens now see the Peshmerga as their true protectors.

Photos of liberation of villages south of Kirkuk.

Please note that a majority of our sources have remained anonymous for security reasons.

Disclaimer: The views, opinions, and positions expressed by authors and contributes do not necessary reflect those on the WKI.